In conjunction with Egham Museum’s ‘Women: Wives, Workers & War’ exhibition which ran from November 2018 – June 2019, Museum volunteer and researcher Geoff Meddelton explores some of the exhibition’s themes in more depth.

Egham was home to a Red Cross Hospital, the Princess Christian’s Military Hospital in Englefield Green, which had VAD (Voluntary Aid Detachment) nurses within its staff.[1] The demands of modern war imposed an enormous additional burden on the medical services available to the military. In the years immediately prior to the outbreak of the conflict, preparations were already being made for a national effort on the part of civilians to assist in the event of a European war. Concerned at the prospect of a shortage of medical personnel should war come, in 1909, the British Red Cross Society and the Order of St John of Jerusalem created the Voluntary Aid Detachment. By 1911, 20 000 volunteer VADs in 660 detachments were being trained under the auspices of the Red Cross Society and Queen’s Nurses (district nurses).[2] In October 1914, a few months after the outbreak of the conflict, the British Red Cross Society and the Order of St. John formed the Joint War Committee to assist in the relief of the sick and injured and to facilitate the recruitment, training and deployment of volunteers.[3] VADs were recruited from either organisation. VADs worked in single sex units, all were trained in first aid, nursing, cookery and hygiene and men were also trained as stretcher bearers and in battlefield first aid. The women VADs were generally between the ages of 23-38, and were operating in an auxiliary capacity under the supervision of fully trained nurses and other medical staff.

To cope with the scale of casualties, it was necessary for there to be a significant expansion of hospital facilities. The Princess Christian Hospital at Englefield Green was established as an emergency or auxiliary hospital. It was rapidly constructed in pine wood (construction took 12 weeks) on crown property at Englefield Green, about a mile from contemporary Egham. By the time of its closure in 1919, some 3400 patients had been treated, of whom slightly over 83% were casualties directly from the Front. The survival rate was high with just 2% of patients dying.[4]

Local support

The only way that the authorities could adapt quickly and effectively to the enormous additional requirement for personnel, financial and material assistance as well as premises was through securing public support. From the beginning of the War, the Red Cross established in every major town work depots to collate and dispatch clothing and medical materials secured through donations collected by local volunteers. The importance of local support can be seen in the provision of the first ever motorised ambulances. As early as October 1914, after only three weeks, an appeal by The Times raised enough funds to buy 512 ambulances.

Women who were prominent in the local community at Egham played a vital role in the mobilisation of popular support for VAD services. In 1915, at a meeting held at Royal Holloway College, in support of establishing an auxiliary hospital at Englefield Green, Miss Higgins, principal of the college, gave her support.[5] It also had the support of Miss Cabrera, owner of Wentworth Farm, Virginia Water and the wives of two farms in the immediate vicinity of where the hospital was to be established. Baroness de Worms (resident of Milton Park Farm, Englefield Green) and Lady Shroeder (resident of Heath Lodge, Englefield Green).[6]

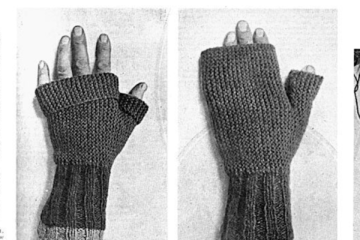

The active support of women and girls in aid of the war wounded was, of course, made manifest in a variety of ways. In November 1914, the ‘National Egg Collection’ for wounded soldiers was established and this involved the support of local communities in reaching a War office target of a million eggs a week.[7] The collection of Eggs in the Egham area was under the direction of the following women- Miss Petrie Merivale (Egham), Mrs Chetwynd Stapylton (Englefield Green), Mrs Forrest (Bishopsgate) and Miss Macmasters (Virginia water).[8] Royal Holloway College, then a ladies’ university college, played an important part in the local effort. Students volunteered as VADs and others ‘knitted comforts for the troops’. In 1915, the college set up its own Red Cross working group to produce hospital clothing and to roll bandages, all in support of the Princess Christian Hospital.[11]

In 1915, Special Service VAD was established to assist the Royal Army Medical Corps (RAMC). This organisation enabled VADS to serve in base hospitals near the front.[12] Local resident Miss Lilian Audrey Forse received recognition for her distinguished service at the general hospital at Wimereaux (No.53; London General Hospital). She received the Military Medal at an investiture ceremony in August 1918.

For courage and devotion to duty displayed when during a hostile air raid a bomb fell on the hospital marquee of which she was in charge. Although great damage was done and many patients injured, she showed admirable coolness in the performance of her duties throughout, and carried on as if nothing had happened.[13]

London Gazette, 4th June 1918. Text of why Lillian Audrey Forse received her Military Medal.

Mrs Maud Chetwynd Smyth and Mrs Molly Forrest were VADs working at the Princess Christian Hospital.[14] Both had played a key role in the organisation of the local Red Cross working party, for which they received the following salutation on their record cards; ‘was first head of the Englefield Green working party which did a great deal of work for the Princess Christian Hospital.’[15] Both ladies were awarded the Special Service Cross.

Being thrust into the limelight, a direct consequence of their public duty role in the Home Front, could bring about unwelcome intrusion into private life. Maud Chetwynd Smyth appears to have had a real sense of community responsibility; in a time when food was scarce and pre-war items became a luxury, she assisted in the purchase of tea for poorer families. However, she was forced to have published a denial and threat of legal action when a news article suggested that she was buying ‘too much tea’. In reference to the allegation, she defended the bulk purchase citing that it included provision for those too poor to buy tea.[16]

Long term implications

The role of the VAD developed as

the conflict progressed. The growing

manpower needs of the armed forces opened up opportunities for women. It was, after all, during this period that

women could, for the first time, study for medical degrees. All VADS had to pass exams to receive their

first aid and nursing certificates.[17] To replace men called up for the forces, a

‘general service’ section of the VADs was established in September 1915 to

perform roles such as dispensers, clerks, cooks and storekeepers.[18] For some women, service in the VAD opened up the possibility

of travelling abroad to serve in hospitals near the battlefronts; from

1915, according to the individual

records of the British Red Cross, women volunteers could be found in military

hospitals in France, Malta and the Middle East . However, other sources show that VADS could

be found in other theatres of operations such as the Balkans and Russia.[19]

[1] www.redcross.org. The British Red Cross Society has digitalised its resources, including the enrolment cards for its volunteers from which a great deal of information can be accessed concerning age/ origins and placements of thousands of volunteers.

[2] ww.independentnurse.co.uk/professional-article/ww1-the-rise-of-the-vads/66221.

[4] LOST HOSPITALS OF LONDON in https://ezitis.myzen.co.uk/princesschristianeg.html Reference should be made to the fact that auxiliary hospitals were to treat the less seriously wounded, more often patients were convalescing and this would partly explain why survival rates were high.

[5] Surrey Herald, 4th June 1915- ‘BIG HOSPITAL FOR EGHAM’ in https://chertseymuseum.org.

[6] Minute Book 28/7/17- 20/2/1918 in ‘Egham and District War Agricultural committees- Surrey History Centre

[7] https://ww1centenary.oucs.ox.ac.uk/body-and-mind/the-national-egg-collection-for-wounded-soldiers-and-sailors-1914-1918/ The campaign, officially sponsored, aimed its propaganda especially at children.

[8] Surrey Herald, 16th April, 1915; ‘EGGS FOR WOUNDED SOLDIERS’ in https://chertseymuseum.org.

[9] Surrey Herald, 29th October 1915; ‘EGGS FOR THE WOUNDED’ in https://chertseymuseum.org.

[10] Surrey Herald, 1st October 1915; ‘THE NATIONAL EGG COLLECTION’ in https://cherseymuseum.org. According to the article, fresh eggs were considered invaluable in aiding recuperation. The importance of the role played by the local volunteer in collecting eggs is alluded to in the following comment ‘at the present time there is hardly an article of food so difficult to obtain.’

[11] www.eghammuseum.org/blg/2018/08/23/lorna-scott-and-her-mortar-board. Interestingly the principal although she played a part in the founding of the Princess Christian Hospital, there is no record of her role in this or any aspect of her support for the local Home Front in her entry for the ODNB.

[12] https://www.longtrail.co.uk. Base hospitals were part of the casualty evacuation chain. There were two types of these hospitals; stationary- located very near front in towns and general. General hospitals were nearer the coast to facilitate movement of casualties to coastal ports.

[13] https://www.greatwarforum.org/topic/39175-nurses-awarded-military-medal. The MM was established in 1916 to be awarded for acts of gallantry and devotion to duty whilst under fire. It had been extended to civilians from June of that year; see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Military_Medal.

[14] https://www.redcross.org.uk . Maud and Molly were at the hospital from June 1915 until December 1918.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Letters to the Editor; ‘Surrey Herald, 14th December 1917; ‘RUMOURS CONCERNING TEA’, in https://chertseymuseum.org.

[18] Ibid.

[19] In 1919, Lilian Forse was on Red Cross duty at Vranja, Serbia.

0 Comments